Uncertainty around immigration, birthrates, the economy and even the environment challenge us to think about not one but multiple US population scenarios.

“The future ain’t what it used to be.” If Yogi Berra had been talking about population projections, he could not have been more accurate in his assessment. It takes a long time to collect and publish census records, so that the latest data is always out of date. Any subsequent analysis of the latest data is of course even more out of date, and updated estimates made in the ten years until the next census will be based on that data and are likely to be wrong.

The effect of Covid on the declining birthrate in the U.S. provides a good illustration of the difficulty. In December 2023, Scientific American ran a piece with the headline “COVID Caused a Baby Bump when Experts Expected a Drop”. An economist was quoted speculating that the pandemic-related hiatus and change in work patterns allowed people the flexibility to start a family.

But then only a few months later in April 2024, official (CDC) data was released that told a different story, summarized by a CBS News headline “U.S. birth rate drops to record low, ending pandemic uptick.”

And this is just a relatively small part of the problem – only considering changes over the very short term. The further into the future we project, the more likely errors become. This is why scenario planning, which considers multiple possible futures, is such a powerful tool for effective strategic foresight, and why it shouldn’t be a surprise that this is an issue we’ve written about before, after the Census Bureau lowered its previous estimate of the 2050 U.S. population by 40 million.

Births, deaths and immigration

The difficulty lies in predicting three things – births, deaths, and immigration, all of which are affected by other things, and which can to some extent affect each other. A declining birthrate (more on the subject here) will mean an ageing population, giving rise to an increased burden of dependency – a larger group of older people depending on the productivity of a smaller workforce. This can be offset by immigration, but in the U.S., as elsewhere, this is a political issue, with conservative-leaning older people (along with enough in middle-aged cohorts) resisting immigration, fearing an unfamiliar society and the unknowns it may bring.

Given the choice between a dynamic but unfamiliar society or a static but familiar one, older people tend to opt for the second, and as they form a larger and larger proportion of the electorate they are likely to hold sway. This would result in a slowly shrinking population, a flat or declining economy and even perhaps some inter-generational conflict.

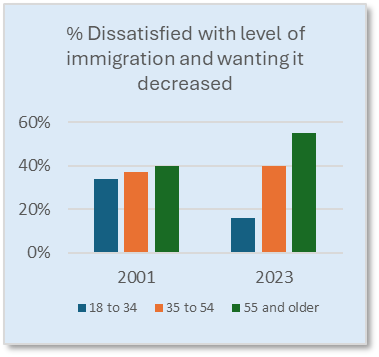

But each of these assumptions might not hold in the future. Suppose the resistance to immigration among older people is a cohort effect, rather than a life stage effect (i.e., it’s to do with the life experience of a particular group of people rather than an automatic product of growing older). The chart shows Gallup data that would support this – in 2001 age differences were quite small but since 2001 dissatisfaction has grown among older people while declining among young adults.

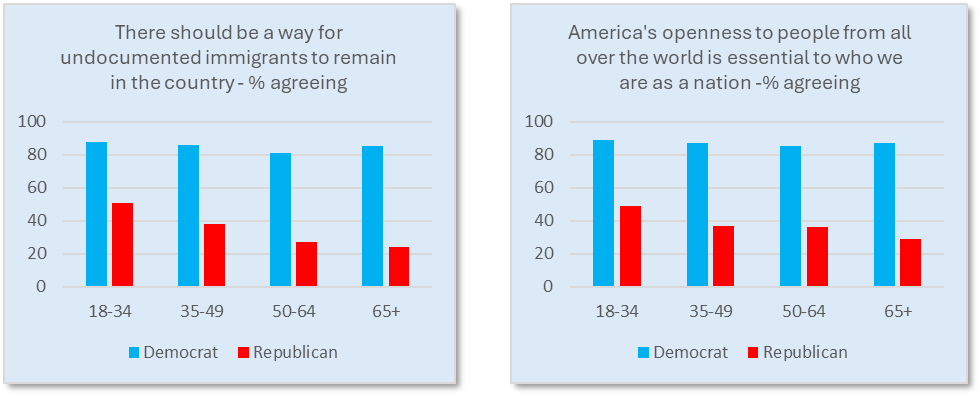

Attitudes toward immigration also seem tightly connected to political leaning. The two charts below (from Pew Research, April 2024) show distinct age effects, but only among registered Republican voters. Their Democrat counterparts are broadly the same in their view, regardless of age.

So a plausible second version of the future might entail a broader acceptance that immigration is key to growth and a core part of the country’s identity, as more diverse, tolerant and less fearful younger cohorts replace the boomers who preceded them. In this case the population decline implied by a lower birth rate might be offset by immigration.

Then of course there are AI scenarios…

So far we haven’t considered technology and AI-driven innovation, and the insulating effect this could have on productivity growth – so that the economy remains healthy regardless of the shape and size of the population. This could attract (or possibly require) immigration and might also allow greater gender balance in domestic childcare which could lift the birth rate, thus bringing us full circle to a more sustained version of what was suggested earlier by the economist during Covid.

Climate change will also affect things – immigration almost certainly, but also domestic migration, in terms of domestic U.S. population shifts. Climate worries, in the extreme, could also turn out to be a disincentive to family formation.

Let’s not forget the effects that population will have on entitlement benefits; nor have we considered the distinction between legal and illegal immigration. So even taking a few of the forces for change and dealing with them monadically and somewhat superficially we can arrive at many different outcomes.

When it comes to population, there is no shortage of future uncertainties to ponder. But we can be sure the reality will be far more complex, more nuanced and likely more politicized as all of these issues begin colliding.

Challenging essay. It’s impossible to get around how important immigration will be as the population ages. Aging boomers will require a larger pool of direct care workers. An expanding workforce will also be necessary to shore up Social Security financing. The current political environment is unfortunately not conducive to the “grand bargain” on immigration necessary to put all this in motion. But at some point these labor and population realities are going to have to be faced.

Indeed. One of the key difficulties is the ‘boiling frog’ nature of the problem. It is slow to appear and easy to put off until later. The problem facing the Social Security trust fund was first surfaced in 1990, but is only now being widely discussed – a mere 30+ years later.

Very stimulating. I think very few Americans are aware of how open immigration was in the era when most of our ancestors came to the United States. I have done some genealogical work for my family over the past few years, and one thing that struck me is how all of my ancestors (all from Ireland, between 1825 and 1897) just simply showed up, and five years later they were citizens. Apparently this was true, for European immigrants at least, until the 1920s, when a very familiar xenophobic tendency found expression in legislation that choked immigration off until a reopening in the 1960s. Linda Chavez had a piece on this fact, which gets lost in the debate over people who “came in the RIGHT way,” recently: https://substack.com/@lindachavez/p-147275060

Also, we old scenario hands used to say way back in the 1990s that demographics was one of the few predictable things about the future, an assumption set around which we could build all scenarios. The future indeed ain’t what it used to be…

Thank you for this, Gerard.

Further contributing to the complexity of thinking about this issue are social attitudes that may have nothing to do with the data and are not susceptible to projection.

For instance, a survey by the PEW Research Center in 2018—two years before anything that could be attributed to COVID—found that the share of U.S. adults younger than 50 without children who said they were unlikely to ever have kids was 37 percent. By 2023 the percentage was 47 percent.

The principal reason given in both surveys was the same: The “unlikelies” simply didn’t want children. Intriguingly, PEW found that substantially fewer women than men thought this would be a negative thing for the United States. (https://tinyurl.com/yw86z654)

This will be a fascinating one to watch, which as you say, Gerard, will ramify in countless unpredictable ways. Demographic trends play out over generations. Over such a time span we can expect all sorts of social (not to mention political) volatility. I wish I was going to be here to see where we end up.